Abstract Expressionist artworks have been understood, by artists and critics alike, as direct manifestations of the artist’s interior states: the work being composed by and, at the same time, serving as the index of an authentic subjectivity. Within this interpretative framework, the painted surface became legible as an inscription of individual freedom, a central value of postwar American cultural ideology.

The consequence of this framework was the identification – or even the symbolic transformation – of the pictorial marks into enlarged signatures. These gestural inscriptions, nonacademic in their refusal of formal coherence and seemingly accidental execution, varying from artist to artist, acquired the function of surrogates of authorial presence. Even in the absence of the conventional signature (typically placed in one of the lower corners of the canvas), the paintings of any given artist differentiated themselves from those produced by others by way of personal style. And so, through the repetition of the same engagement strategy of the canvas, the entire painted surface operated as a marker of identification.1

Invariably, the psychological and biographical explanations produced a cult of personality that enforced the public’s fascination with the artist as a bastion of individuality. This dynamic consolidated the notion that the artist’s identity – their touch, their name and, correspondingly, their signature, whether actual or, as discussed, stylistic – automatically invested any canvas, any object with the status necessary for it to be a valuable, sacred artifact. During the heyday of the New York School, the autographic inscription thus became the principal currency of aesthetic valuation: the reason for the relentless pursuit among artists of personal expression as a means of differentiation, a way of distinguishing their artistic mark (locally and historically) from all others.

In the midst of all this, where does Robert Rauschenberg’s experimental erasure of a de Kooning drawing stand? In 1953, within New York – the newly established center of the art world – Abstract Expressionism enjoyed great appreciation and commanded immense cultural authority. The artworks of artists such as Jackson Pollock, Robert Motherwell, Jack Tworkov, and Willem de Kooning had come to represent not merely a new tradition but the language of the avant-garde itself: the vehicle through which the ideology of the personal mark and the mythology of authentic genius found material expression.2

Though different from his peers – as is the case with many innovative artists –, Rauschenberg adopted a position of resistance (though not entirely hostile or aggressive) toward this newly dominant tradition, choosing rather to engage critically with the values Abstract Expressionism proposed: particularly the mythologizing of gesture and the elevation of creative tension into a profoundly heroic act.

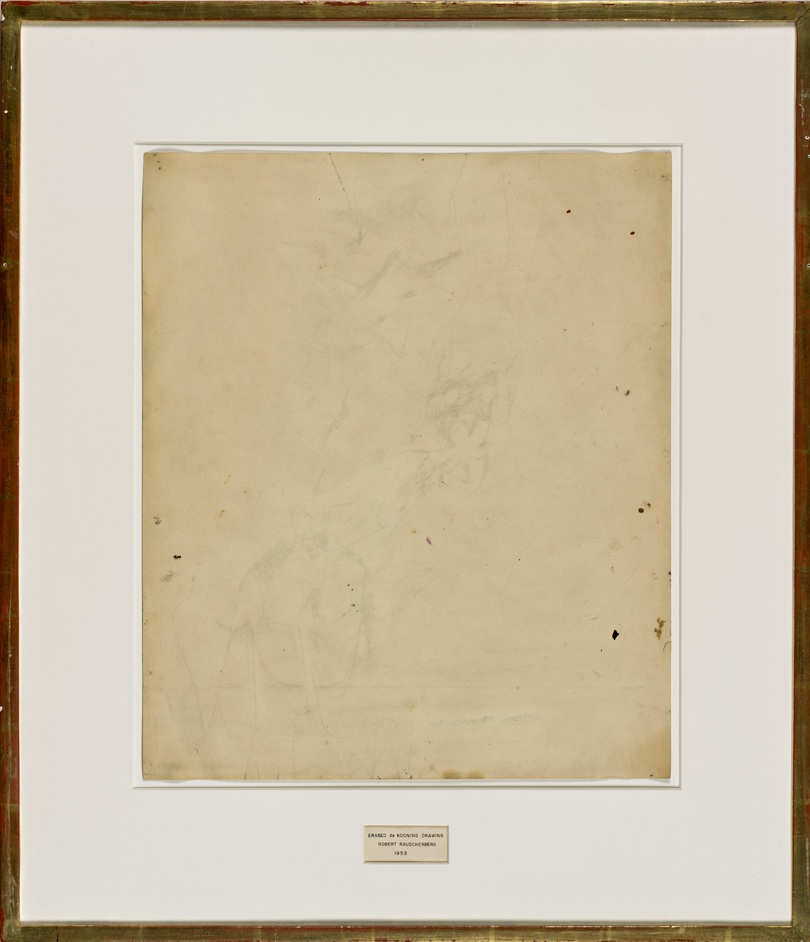

Considering de Kooning’s stature during this period, the presumably “destructive” act that resulted in the Erased de Kooning Drawing of 1953 was labeled nothing short of scandalous, operating for critics and spectators alike as harbinger of the nihilism that had defined Dadaism. However, considered from another, this time “constructive”, perspective – one that might reveal the work’s inherent parodic dimension – the act of erasure must be recognized as being appropriated from de Kooning’s own technical repertoire. After all, de Kooning’s signature practice, his fundamental modus operandi, was precisely to erase each day’s work.

Robert Rauschenberg, Erased de Kooning Drawing, 1953. Traces of drawing media on paper with label and gilded frame, 64.3 × 55.4 × 1.3 cm. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco.

If Rauschenberg’s gesture could be compared to a damnatio memoriae, it should not be understood as an attack on de Kooning’s person, art, or personality – in fact, Rauschenberg received the drawing from the Dutch artist himself and maintained friendly relations with him – but rather as a critique of the ideological framework that de Kooning’s public figure (along with the other Abstract Expressionists) had set and come to represent. Namely, it was an attack targeting the elevation of autographic style and authorial presence into the principal criteria of appreciation.

As the act of erasure was performed not by de Kooning – as public expectations had been conditioned to assume – but by another hand, a critical question emerges: who is the rightful author of the Erased de Kooning Drawing? While an answer to this question will not be given here – not by ourselves and not directly, that is – it should be noted, in anticipation of what follows, that Rauschenberg’s gesture substantiates the rejection of authorship as such, and specifically challenges the limiting notion of authorship as individual labour rather than collective practice.

Such a challenge of authority – a concept that refers both to the figure of the author (as artist, in our case) and to authority as the power to command or convince – emerged amid conditions set to transform the art world and its historical development once again. First, Abstract Expressionism had already, in the 1950s, begun its inevitable decline, gradually losing its avant-garde status. Second, interest in Dada was resurging in the New York area, catalyzed in part by Robert Motherwell’s 1951 anthology entitled The Dada Painters and Poets – a collection that assembled together texts and testimonials by European artists associated with the movement.

Among the prominent figures featured in Motherwell’s anthology was, unquestionably, Marcel Duchamp: a local figure, the French artist having made New York’s Greenwich Village his home in 1942. Both physical and textual, Duchamp’s presence within the context of American art proved decisive in challenging the newly established hegemony of Abstract Expressionism and its consolidated frameworks and habits.

After World War II, the readymade and its associated logic, deeply tied to Duchamp’s legacy, had already begun to assume an important consideration in art history, considered by some – Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns among them – as equaling in importance the canonical achievements of Surrealism and Cubism. Through this recognition of the readymade as a valid artistic practice and the assimilation of its teachings – through these sudden shifts in the cultural conjuncture, and against the grain of his artistic formation, which should have aligned him with Abstract Expressionism – Rauschenberg’s work congealed into a distinct and visionary creative system. Its essential innovation was to produce “a kind of painting in which the artist – his personality, his emotions, his ideas, his taste – would not be the controlling element,”3 or from which these subjective elements were altogether absent.

Through this absentness of subjectivity by which the author achieves his famous and metaphoric death,4 Rauschenberg transformed, once again, the Duchampian practice of the readymade into an exemplary model for creative indeterminacy. From early monochromatic experiments such as the White Paintings (1951), which signal the absence of the artist’s mark and thus of authorial presence, to later neo-Dadaist collages like the Combines series (1954-1964) or Signs (1970): the latter coldly registering the events of the past 1960s decade without subjective investment or evaluative criteria – these works defining Rauschenberg’s career demonstrate the indeterminacy that enacts the death of authorial interpretation and withdraws all claims to definitive meaning.

As is now well recognized, with Duchamp the process of selecting a work of art gained momentum and was able to achieve parity with the status previously reserved for “making” or “creating” it.5 The implication was that, from Duchamp onward, there could no longer exist – or rather there was no longer a valid basis for – a difference in value between an object created by an artist and one produced by someone else. After all, since both types of objects must pass the selection stage in becoming art, there exists no intellectual, ethnical, or aesthetic difference between an artist’s decision to select their own created work, a curator’s selection of specific artworks for exhibition, and an artist’s selection as art of any randomly encountered object they did not themselves in fact create. Summarizing this condition, Boris Groys states: “Today, an author is someone who selects, who authorizes. The author has become a curator.”6

Let us consider for a moment Duchamp’s conception of the readymade as critical instrument. Through the consecration of otherwise banal or, in Groys’s terms, profane objects – Bicycle Wheel (1913), Bottle Rack (1914), Fountain (1917) etc. –, the French artist enacted (much like Rauschenberg would after him, as discussed) an institutional critique of the art world: interrogating the very authority that presumes to determine what constitutes art and what doesn’t, and what merits exhibition. In what way?

It is well known that in April 1917 Duchamp’s Fountain – or rather, the porcelain urinal signed by Richard Mutt, a pseudonym – was never displayed in the exhibition area staged at the Grand Central Palace by the Society of Independent Artists. And this refusal reveals exactly the readymade as institutional critique rather than merely experimental practice.

Had Duchamp signed the urinal with his own name, the commission would almost unquestionably have accepted the work into the exhibition. The established reputation of the French artist – who was himself, alongside others, a member of the society’s board – would have carried sufficient authoritative weight to ensure the Fountain’s display. However, by presenting the urinal instead under the name of the fictitious R. Mutt, the work appeared to lack the necessary credentials required for its recognition as art. What this episode revealed was that institutional validation depended less on the object itself (its intrinsic qualities) than on the artist’s established reputation.7

Thus, whether the readymade is recognized and legitimized as art depends on the authority of its author – their name, reputation and prestige (all of which R. Mutt noticeably lacked). This question of authority suggests, among other things, that the readymade’s (the object-became-art) properties are secondary, insignificant in comparison with the artist’s name: that the legitimizing power is in fact a human authority.

Although the readymade was chosen through an uninvolved, disinterested act on the part of the artist: one that asserted to have escaped cultural exigencies regarding good or bad taste, exceeding standard definitions of art –, this decision does not, in fact, escape the involvement of anthropic exigencies. It doesn’t escape the human – be it subjective – judgements about what can or cannot be considered art. In this sense, the selection of the readymade within the limits of human (subjective or not) interest may only be read as a triumph of intellectualism over cultural constraints, of the Idea over its material actualization. This was what Duchamp intended for. In the case of the Fountain, the work escapes the grotesque connotations ordinarily associated with an urinal and attains sculptural status by virtue of the author’s act of selection, through its consecration.

Concerning the Duchampian readymade, its anthropocentrism is maintained by the obligation that the human authorial contribution be embedded in and recognized as part of the art object’s essence. Present through the signature – whether real, stylistic, or pseudonymous – the anthropic aspect persists and overtakes the object’s whole existence. For Marcel Duchamp, the signature’s role was to index the temporal moment of the chance encounter by which the object was selected. Through this act of indexation, the moment of selection is conferred a temporal significance that suspends and subordinates all the moments that follow. In other words, the moment of selection assumes a prominent place in the history of the readymade.

In this sense, the existence of the consecrated object becomes (artistically) significant only after it receives the attention of the human subject. This condition, deeply rooted in Cartesian dualism,8 corresponds to the position of the transcendental subject for whom the world exists solely within the limits of their faculties and experience. For such a subject, the non-human must respond and transform itself (or allow itself to be transformed) to be rendered significant: that is, it must be handled, domesticated, subjugated, whether literally or metaphorically. Consequently, the signature – resembling in nature livestock branding – signals the perennial presence of the human on the body of the artwork. Perpetually invoked, this human concept obscures the material dimension of the artwork, its intrinsic thingness.9

Returning to Rauschenberg, the Duchampian principle of indeterminacy reemerges. However, while the American artist was indeed also selecting – an thus exercising a form of authority –, he was not imposing his subjectivity and identity upon the object. He was not enforcing control. He was not directing or foreseeing the object’s future development. In other words, certain (not all as a rule!) readymades recognized under Robert Rauschenberg’s name are not actually “(al)ready-made”, but rather continuously “(in the) making”.

Regarding the time of selection, the indexation of the chance encounter: it isn’t important. This is because the time of selection, making and consumption (of viewing by the spectator) coincide:10 the work of art produces – selects, makes, consumes – itself perpetually.

Such staging of presence as perpetually evolving was central to Rauschenberg’s art. As Rosalind E. Kraus articulates it: “Rauschenberg was insisting upon a model for art that was not involved with what might be called the cognitive moment (as in single-image painting) but instead was tied to the durée – to the kind of extended temporality that is involved in experiences like memory, reflection, narration, proposition.”11

The diagnostic would then be an autopoietic12 process through which the work of art, as non-human entity, transforms itself from moment to moment in the absence of any external influence or authority that initially selected it for exhibition. Through such an autopoietic becoming, the art object loses its resemblance to itself – to its former self at the moment of selection. It escapes fixation and permanence.

How exactly, what do we mean by all this? Around 1953, Rauschenberg participated in an exhibition whose theme was the return to the great lost and nostalgic subject of “nature in art” – yet another instance of art history’s periodic retour à l’ordre following all the modernist experimentation. With his characteristically dissident spirit and out-of-the-box thinking, Rauschenberg treated the theme literally: presenting a patch of dirt and vegetation sustained inside a boxlike frame and held up by wire as a painting.13 This work, entitled Growing Painting (1953), was part of the artist’s Elemental Paintings through which he – financially precarious at the time – anticipated certain precepts of Arte Povera and the Environmental movements while, additionally, addressing one of the most important dilemmas: „«what is a picture and what isn’t?»”14

In collapsing the distinction between painting and sculpture (as object), Rauschenberg enacted what Joseph Kosuth would later theorize as the essential artistic contribution: questioning the nature of art itself. As Kosuth affirmed, the «value» of particular artists after Duchamp can be weighed according to how much they questioned the nature of art; which is another way of saying «what they added to the conception of art» or what wasn’t there before they started.”15 By declaring Growing Painting to be “indeed a painting,” Rauschenberg expanded the modes through which art can be conceived.

It is in this way that Rauschenberg’s practice manifests his own assertion: „«I’ve always felt as though, whatever I’ve used and whatever I’ve done, the method was always closer to a collaboration with materials than to any kind of conscious manipulation and control.»”16

Going against the conception that an artwork must always be thought in relation to its creator, always mirroring, through its presence, the image of its author, Rauschenberg’s practice eliminated conventional markers of authorship. Beyond the implicit and literal existence of the work, no gestural mark could be found, no deliberate modification evident, no signature or index of presence or passage. The artwork was becoming through temporal unfolding, through immanent development, in the absence of anthropic intervention – always dissimilar, always differing.

An instance of Rauschenberg’s collaboration with materials is found in Dirt Painting (for John Cage) (c. 1953). Upon close analysis, the mold – in places yellowish, in others bluish – has developed organically and irregularly across the dirt surface, dominating the composition and consequently overshadowing any human action through which the work came into being. This mold, entirely non-human, rivals in power the human signature of authorship, which, as we have argued, obscures the work and invokes the author. It might be noted that, in Dirt Painting (for John Cage), the effect might be the same but the roles are reversed: the non-human – the mold – imposes itself over the surface of the work as if signing its own creation. The mold claims the canvas-like surface and paints over it, hiding Rauschenberg’s presence, obscuring his name: Rauschenberg’s authorial presence is subsumed by the mold’s direct presence.

Robert Rauschenberg, Dirt Painting (for John Cage), ca. 1953. Dirt and mold in wood box, 39.7 x 40.2 x 6.4 cm. Robert Rauschenberg Foundation.

Returning to Growing Painting, we might observe that it relies on a similar artifice, though articulated differently and by a different set of actors: „Later, when some birdseed that had accidentally fallen into a dirt painting began to sprout, he got the idea of making a «living» picture, with real grass and moss.”17 The accidental event that produced the work can thus be understood, on equal terms, as both an act of making and one of selecting. Here, the effects of nature – meaning the outcomes of the event’s contingent character – replaced any intention that the artist might have had. Rauschenberg had, in fact, intended to make a Dirt Painting, not a Growing Painting. The consecration of the small patch of dirt contained inside the boxlike frame as Growing Painting was the result of a creative event in relation to which Rauschenberg’s role was less that of an author, and more that of a spectator.

The dirt, the seeds, and their encounter effectively created and selected themselves. Accordingly, it was not Rauschenberg’s own idea that determined the selection; rather, the event itself – witnessed and acknowledged by him – unfolded on a distant scene and, enacted by a group of non-human actors indifferent to artistic intention and untrained in any artistic sense, decided in his place.

This calls for a renewed effort of thought. A reconsideration. As humans bound by tradition and old rules, we are compelled to accept the reachable but insolent claim that Robert Rauschenberg is in fact the creator of the artwork. His name, after all, is the one invoked when thinking or discussing the work; he is the figure credited with bringing the event into the exhibition space. But is Rauschenberg here truly an artist or, as Boris Groys suggested, more of a curator? For if we are to abandon our anthropocentric preconceptions, it becomes clear that Growing Painting emerged from a chain of events – the dirt’s position, the seed’s fall, the process of germination – in which agency was distributed, more or less equally, among human and non-human actors. The artwork, then, exemplifies a network in which authorship is not singular, but shared.

Rauschenberg’s watering of Growing Painting during its exhibition might add to this reading of the process as “curating”: especially in the original Latin sense of “taking care of.” This gesture underscores the American artist’s role as a facilitator rather than creator: selecting certain organic processes and introducing them in the space of the gallery. Moreover, if we’re to look at the artwork’s autopoietic life, it seems the non-human’s agency won out over the human’s: this is because, despite Rauschenberg’s efforts to maintain the picture “growing” (alive, green), it eventually dried out. The painting thus proved a life and will of its own, resisting human intention.

Lacking finality. Resisting identity. Dirt Painting (for John Cage) demonstrates the same principle: the mold grown on the dirt surface – spoiling, deteriorating the artwork, as mold implies these kinds of connotations – is actually evidence that “art makes itself”. Such an artistic direction is another example for what later came to be called distributed or multiple authorship,18 and being an early part of a protest against “the traditional cult of artistic subjectivity, the figure of the author, and the authorial signature […] a revolt against the power structures of the system of art that find their visible expression in the figure of the sovereign author.”19

This transformation in modes of expression tied to Rauschenberg’s practice can offer valuable lessons. It changes, for example, the question of art conservation, acquiring new dimensions. It teaches that the cracks in an oil painting, the gradual changing of its colors, the tears in the canvas, the breaking of marble, the oxidation of bronze, or even the falling of Venus’s arms etc. could all be seen not as problems or setbacks, as obstacles to art appreciation and enjoyment, but as new forms belonging to a fresh way of understanding the nature of change and making.

Because, reaching this point, the question must be raised: what is superior about one specific condition or moment in the life of an artwork – the moment when the object was deemed finished by the artist, taken down from the easel and placed on a wall, or moved from the studio onto a museum’s pedestal – when compared to all other past or future moments in its existence? Through time, and even beyond human extinction, the art object (or any object) travels alone, autopoietically, without finality and with indefinite potential.

- Such a means of differentiation would have functioned far less effectively in the case of academic art, as an example, which adhered to rules designed precisely to mask the artist’s mark rather than reveal it: pigment and brushwork were to remain invisible, subordinated to the production of verisimilar representation. ↩︎

- Hal Foster et al., Art Since 1900. Modernism, Antimodernism, Postmodernism, London, Thames & Hudson Ltd., 2020, p. 430. ↩︎

- Calvin Tomkins, The Bride and the Bachelors. Five Masters of the Avant Garde, Harmondsworth, Penguin Books Ltd., 1968, p. 204. ↩︎

- We make reference here to Roland Barthes’s essay “The Death of the Author” (La mort de l’auteur), which argues against traditional literary criticism’s practice of relying on the intentions and biography of an author to definitively explain the “ultimate meaning” of a text. Instead, the essay emphasizes the primacy of each individual reader’s interpretation of the work over any “definitive” meaning intended by the author. ↩︎

- In this way moving away the term of “art” from its etymological Latin root of ars, underlining art as “craft, handicraft, occupation”; something created, in any way, by use of hand and/or skill, rather than chance and intellect. ↩︎

- Boris Groys, „Multiple Authorship”. In Barbara Vanderlinder & Elena Filipovic (eds.), The Manifesta Decade: Debates on Contemporary Exhibitions and Biennials, Cambridge, The MIT Press, 2005., pp. 93-94. ↩︎

- Of course, the exhibition included works by artists who were not well-established names in the art world, since entry was, in principle, free. Yet this only underscores the idea that innovation and experimentation were (and are still) mostly limited to those that had already secured recognition and legitimacy. ↩︎

- Through Cartesian dualism, the privileged capacities of language and reason – by which humans distinguished themselves from other things (and, by implication, from animals) –, granted humanity the position of external observer from which measurement and control could be exercised over matter. Limited to our talks, this privilege of reason and language permits human authority to determine what falls under the concept of art. [See Christopher N. Gamble, Joshua S. Hanan & Thomas Nail, “What Is New Materialism?”, Angelaki, Vol. 24, No. 6, 2019, pp. 111-134.] ↩︎

- Here we might note explicitly, and again, that this signature doesn’t need to be literal: it can operate at the level of the spectator who views the readymade (or any artwork) either through knowledge of its history or authorship, or through recognition of the context of its appearance: within the space of an exhibition, for example. ↩︎

- Yet the artwork isn’t produced through consumption! The act of consumption does not create the artwork here, as would be the case in later, contemporary, artistic practices. ↩︎

- Rosalind E. Krauss, “Rauschenberg and the Materialized Image”, Artforum, vol. 13, nr. 4, 1974, p. 37. ↩︎

- From ancient Greek, αὐτo- (auto-), meaning “self”, + ποίησις (poiesis), meaning “making, creation”. ↩︎

- Leo Steinberg, “Reflections on the State of Criticism”. In Branden W. Joseph (ed.), Robert Rauschenberg, Cambridge, The MIT Press, 2002, p. 29. ↩︎

- Calvin Tomkins, op. cit., p. 209. ↩︎

- Joseph Kosuth, “Art After Philosophy”. In Joseph Kosuth (autor) & Gabriele Guercio (ed.), Art After Philosophy and After. Collected Writings, 1966-1990, Cambridge, The MIT Press, 1991, p. 18. ↩︎

- Calvin Tomkins, op. cit., p. 204. ↩︎

- Ibidem, pp. 208-9. ↩︎

- The concept of distributed authorship was first used by British artist Roy Ascott to refer to an online work of art (New Media) in the making of which various artists from around the world contributed: each artist playing the role of a participant with the dual function of sender-receiver. ↩︎

- Boris Groys, op. cit., p. 96. ↩︎